Last month, secretaries across departments presented a blueprint for the 25 identified sectors for the Make in India initiative to Prime Minister Modi. Some of the proposals include direct tax exemptions during the first three years for micro, small and medium enterprises, tax holiday for local manufacturing of defence and aerospace products, SOPS for R&D, and tax benefits to attract electronics and telecom manufacturers among others. According to the campaign website, Make in India is ‘a major new national programme designed to facilitate investment, foster innovation, enhance skill-development, protect intellectual property and build best-in-class manufacturing infrastructure.’

“Make in India is a good initiative but it depends a lot on which state we are looking at. Certain states in India such as Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Chhatisgarh have made greater strides than others. This needs to be taken into account, considering that Make in India is a central government initiative,” says Anirudh Dhoot, director, Videocon. He adds, “From an electronics industry point of view, the campaign is a strategic initiative. Some companies depend too much on imports for parts, which can be minimised. But things are definitely improving. In Maharashtra, we required 50 to 60 permissions before going ahead with anything. Now the number has dropped to ten or twelve.”

Make in India has an ambitious vision but there are a few obstacles that stand in its way and foremost among them are inadequate infrastructure and manpower. Pankaj Kulkarni, director, JSW Cement adds, “In the last decade, the country’s growth was mainly driven by the service sector and manufacturing had taken a backseat. This has resulted in engineers from the best engineering colleges and managers from the best management institutes joining the service sector and not manufacturing. The country on one hand stopped producing skilled technicians, but on the other, is flooded with unemployable university graduates. It is high time that our education system is reformed by introducing a dual education system and vocational schools in line with the German model,” he suggests.

How can the industry and the government contribute to actualising the Make in India campaign? Debi Prasad Das, senior VP – HR, CEAT Limited answers, “The typical roadblocks would be difficulty in setting up business, unfavourable policies like retrospective tax, delay in project set up, litigations related to land, poor infrastructure, a lack of available skills and corruption. The industry should invest in developing skills and research on technology, set-up plants in rural belts, work with local government to improve infrastructure, adapt villages, schools and colleges as part of their CSR to impart quality education in rural areas.” He lists a few measures that we, need to take:

- Bring in the required reforms like labour reforms, make good infrastructure available, reduce red tape for clearances;

- Build the required skills in the workforce and offer strong vocational training and skill-building;

- Invest in R&D; create world-class quality, achieve mastery in technological advancements and develop research-oriented curriculums.

But can India really usurp China’s economy’s position? “A 2013 study from Deloitte’s global index for 38 nations indicates that India is the fourth most competitive manufacturing nation, so the ground is ripe to make India into a manufacturing hub,” opines Rajiv Rajvanshi, sr VP - corporate strategy, Jindal Stainless Limited. “The infrastructure sector will have to prepare the ground for other industries to follow suit. But the focus of the government policy should also be to prioritise and ensure full domestic capacity utilisation, especially in all the core sectors, only then can we truly have a successful Make in India campaign,” he avers.

An academic perspective

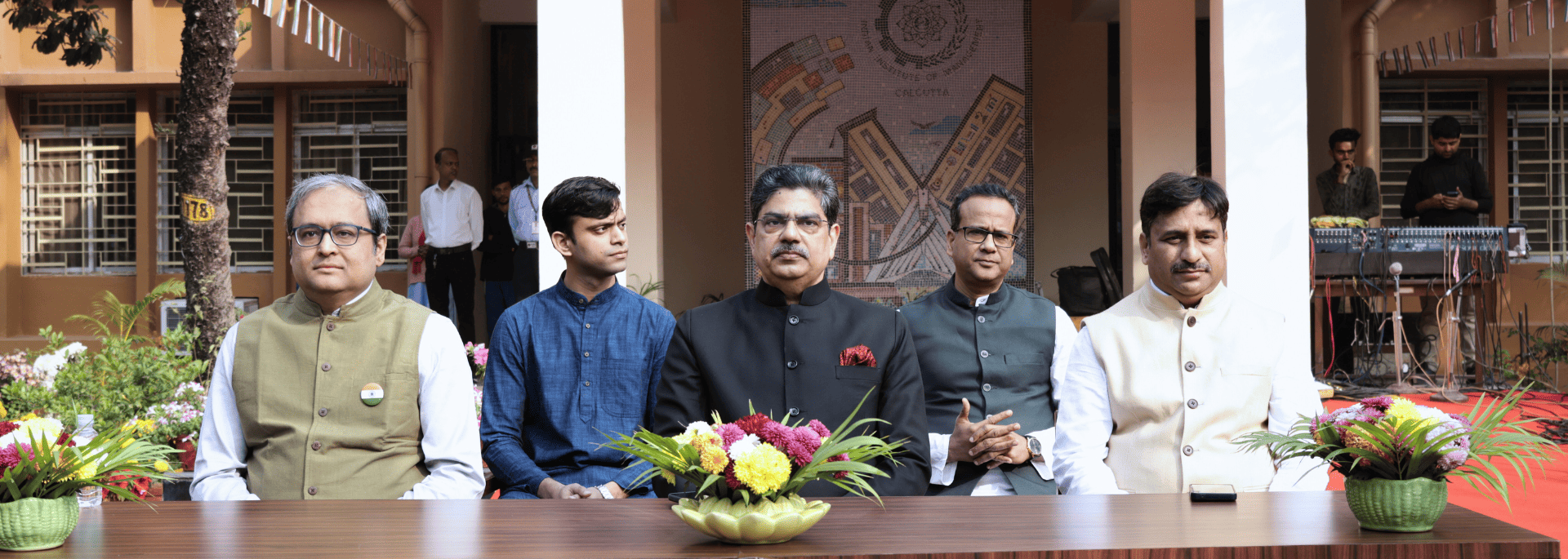

An emphasis on the retail sector spawned a renewed interest in MBAs and other courses with a specialisation in retail. And according to Partha Priya Dutta, chairman of the PGPEX-VLM (Post Graduate Programme for Executives for Visionary Leadership in Manufacturing) offered at IIM Calcutta, the total number of applicants for the programme this year is 140 compared to 110 last year. Dutta lists a few ways through which institutions can help in making the Make in India campaign a success:

- Setting up industry-led research centres, which will complement the academic practices with implementation/execution experience. Also, such centres can serve as knowledge bases for disseminating best practices across the world to the industry;

- The government can fund Centres of Excellence in IIM and IITs for creating value-adding processes from business strategy to technology management, thus focusing on the full-range of manufacturing research bringing world-leading industries, academia together in India. This is essential to build a competitive advantage in Indian manufacturing.

It will certainly be refreshing to see the ‘made in India’ label on every product on the shelf, for the consumers and professionals in the manufacturing industry.

Recent policy measures and projects to open up India’s manufacturing sector:

- 100 per cent FDI allowed in the telecom sector;

- 100 per cent FDI in single-brand retail;

- Validity of industrial license extended to three years;

- For all non-risk, non-hazardous businesses, a system of self-certification to be introduced;

- Process of obtaining environmental clearances made online;

- The Government of India is developing the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) as a global manufacturing and an investment destination utilising the 1,483 km-long, high-capacity western Dedicated Railway Freight Corridor (DFC) as the backbone.